Global warming is directly influencing humans through surface temperatures, but most heat uptake occurs in the ocean. It is therefore interesting how the ocean heat content has changed over time. In a recent article in Science Rosenthal et al. present a temperature record of western equatorial Pacific subsurface and intermediate water masses over the past 10,000 years that shows that heat content varied in step with both northern and southern high-latitude oceans. The findings support the view that the Holocene Thermal Maximum, the Medieval Warm Period, and the Little Ice Age were global events, and they provide a long-term perspective for evaluating the role of ocean heat content in various warming scenarios for the future. This result conflicts with the one of Pages 2k consortium in Nature Geoscience earlier this year where they state: “There were no globally synchronous multi-decadal warm or cold intervals that define a worldwide Medieval Warm Period or Little Ice Age”.

Category: Climate

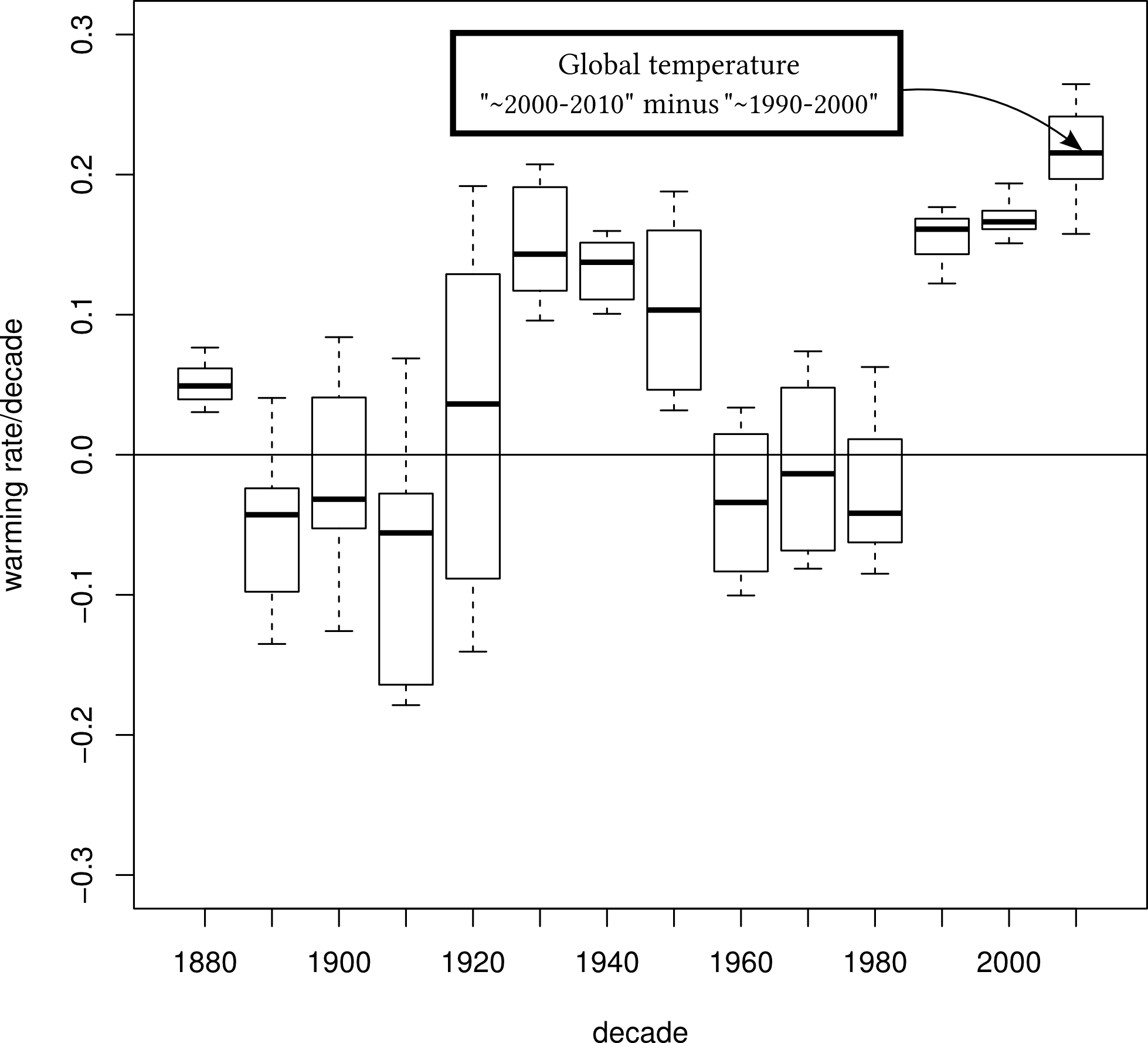

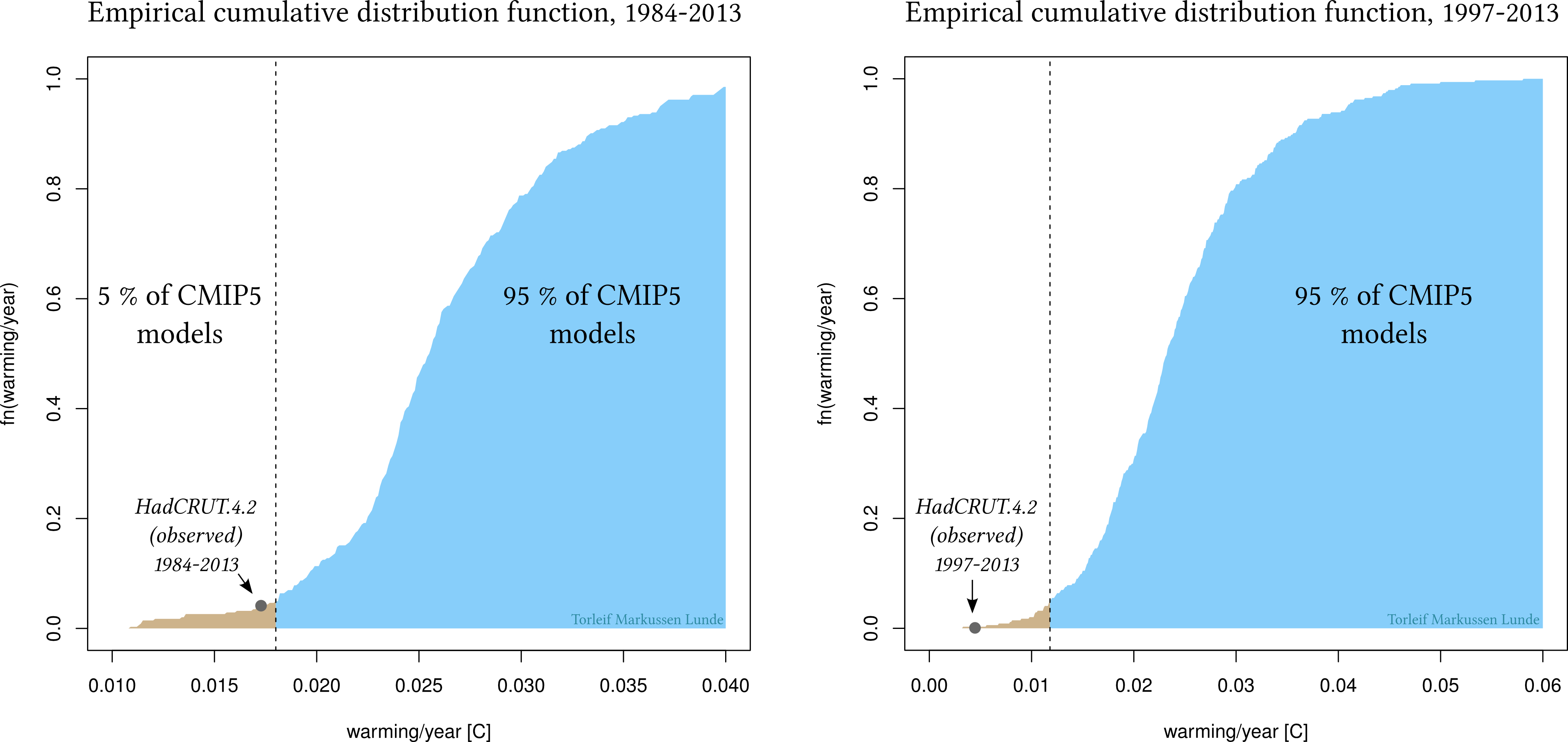

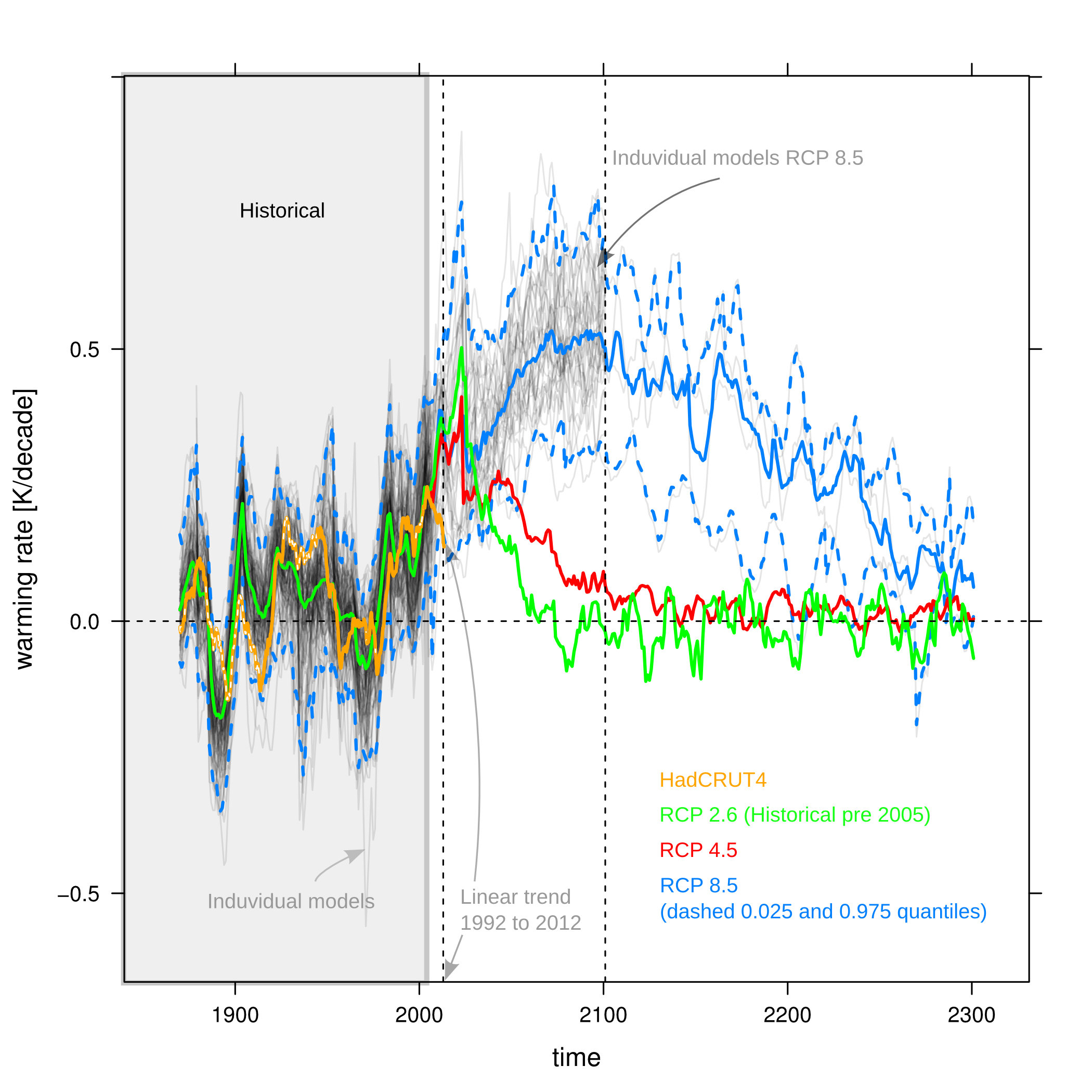

In the discussion about the rate the planet is warming it is tempting to pick single years, and say the models are not correct, you blotted your copybook, the planet is not heating as fast as models predicted, and it will probably not become as warm as the models say. At the moment, we have 20 year period where the median warming rate of 36 CMIP5 models is about 0.15 degrees Kelvin/decade higher than observed. Figure 1 is showing the real and modelled warming rate from 1870-2013, and the modelled up to 2300 using three of the RCP scenarios. It is evident the observed warming rate the last 20 years does not match the modelled ones.

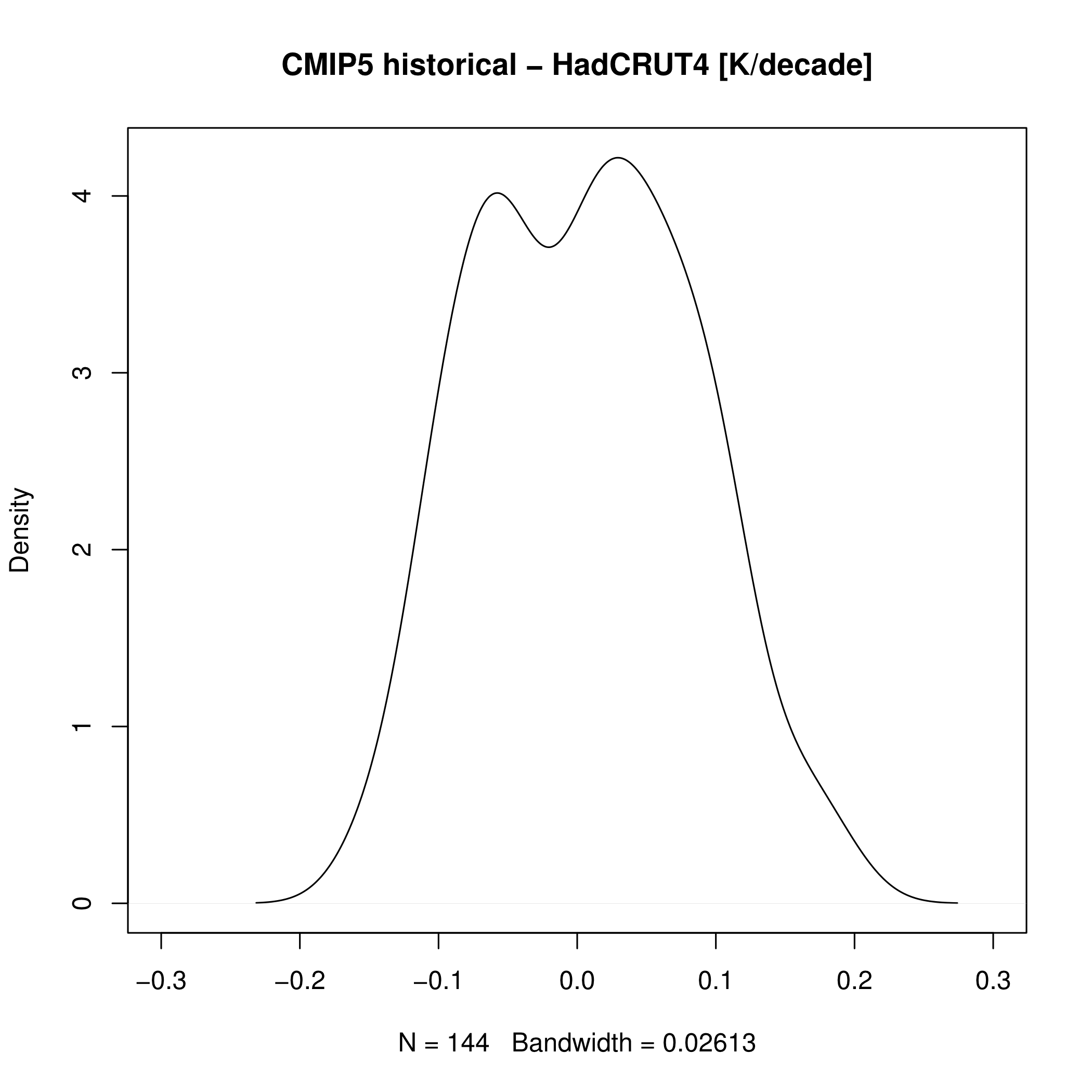

So what do we expect? We do not expect the difference in warming rate to be zero all the time, but we expect that at some points in time the models will warm/cool the planet too fast, and sometimes too slow. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the difference in warming rate (CMIP5[median] – HadCRUT4), and a Shapiro-Wilk test of normality suggest we can not reject the data is not normally distributed. The figure shows that sometimes the models will warm/cool the planet too fast, and sometimes they will warm/cool it too slow, and “it is normal”. Anyway, the main message from the models should be clear; no cooling in sight. I also recommend reading this post about warming rates.

Climate and cherries

In a recent blog post at Climate Lab Book a recent press release by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) describing recent global temperature changes were discussed. Ed Hawkins makes a point about the definitions of a decade (from 2001-2010, 2000-2009, etc.) alters the conclusion of the report. He finds the largest change in temperature between decades is not to the most recent decade as claimed by WMO, but from 1987-1996 to the average of 1997-2006, at +0.24K.

The definition of a decade is cultural, and the result of such analysis clearly is dependent. To explore his ideas further, we define a decade as having 85 different starting and ending points, but all covering a period of 120 months. This means the last decade can be defined as 1996.05.16-2006.05.16, 1996.06.16-2006.06.16, …, 2003.05.16-2013.05.16. This will give us a distribution for each decade and hence limiting the issue of decade definition.

- Figure 1: Warming rate per decade

Figure 1 shows the warming rate between two decades, and it is evident the warming rate was greatest between 1990-2000 and 2000-2010. It is also evident the WMO statement “The decadal rate of increase in the global temperature accelerated between 1971 and 2010” is correct, but the picture is different if we expand the period to 1961 to 2010. The greatest change in warming rate happened from approximately the period (1970-1980/1960-1970) to (1980-1990/1970-1980), so I think we still see some cherry picking, with WMO and Climate Lab Book liking different cherries. Still, no doubt it is becoming warmer…

The common solution

In a recent article in GRL, Emerging selection bias in large-scale climate change simulations, Kyle L. Swanson describes how experiments might go wrong as we seek a desired solution. He hypothesise a common wish to reproduce the recent warming in the Arctic, has lead to less diversity among models with convergence towards some common solution.

He writes the current generation ensembles of model simulations are statistically inconsistent with the observed shifts in in both the mean surface air temperature as well as the frequency of extreme monthly mean temperature events due to climate warming, despite a marked reduction in the spread among ensemble members that by itself suggests convergence towards some common solution. This convergence indicates the possibility of a selection bias based upon warming rate.

I particularly liked his example of what happened after Robert A. Millikan’s original measurement of the charge of the electron: “Millikan’s original measurement was slightly erroneous due to the use of an incorrect value of the viscosity of air. In the decades following Millikan’s work and his subsequent Nobel Prize, other investigators empirically measured the electron charge. When they got a number that was too high above Millikan’s, they thought something must be wrong–and they would look for and find a reason why something might be wrong. When they got a number close to Millikan’s value they didn’t look so hard. And so they eliminated the numbers that were too far off, and did other things like that.”

In our paper in Malaria Journal, A dynamic model of some malaria-transmitting anopheline mosquitoes of the Afrotropical region. I. Model description and sensitivity analysis, we touch upon this issue by stating “A model is mental copy that describes one possible representation of a system… We present an alternative formulation of the dynamics of An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis… if malaria modelers move towards the ensemble thinking widely adopted in the climate community, this model could be one representation of historical and future changes for malaria. The aim of such an ensemble would be to deal with uncertainties in the system. Ultimately, the goal would be to produce policy-relevant information including uncertainty.”

The basic principles of climate are quite easy to understand; the sun is heating the Earth, with more radiation hitting the equator compared to the poles. Seasons are caused by the tilt of the Earth’s rotational axis away or toward the sun as it travels through its year-long path around the sun. From there you can add clouds, water, ice, land masses, aerosols, precipitation, and even mountain and building shadows if you are interested in local weather. The dynamics of malaria can be simplified in the same manner; an uninfected mosquito bites an infectious human, lives for about ten days, and from that time it can infect new humans every time it bites a human. From this simple model it has been demonstrated that killing mosquitoes is an efficient way of reducing malaria, but it is not able to tell us how efficient. To get a realistic representation of how emissions of greenhouse gasses influence climate, or how malaria is reduced by distributing bed nets we need more complex models together with observations. As we add more realism to the system, we also parameters with uncertainty, uncertainty which was there from the beginning, but which becomes visible as we describe them. If we intended to use an ensemble of models to estimate the effect of for example bed nets against malaria, we could get a very precise estimate if all models were identical, or measured their success by managing to keep malaria away from South Africa (many malaria models predict malaria is widespread there). There are still many things we do not know about malaria, and I hope modellers of malaria do not do the same mistake it seems like global climate models are moving towards; a common solution due to wrong reasons.

A couple of days ago I saw this tweet:

https://twitter.com/francetim/status/330978126211465216

I agree with Tim France, but with the short tweet he also assumes UK will be a rich country with a good health system in 100 years. Below are some thoughts on how we evaluate the impacts of climate change, following up a previous post.

Every time driving a car, there is a chance you will crash. In thunderstorms you might be hit by lightning, and at any time your home could be hit by a meteor. If you drive faster the consequences of a car crash is probably more severe; if you fill your pockets with iron and stand under a tree in a thunderstorm that might be a bad idea; we can increase or reduce the risk of something bad happening. For meteors, well, there is currently not much we can do. What all of these threats have in common is the low probability they will occur, but if they do the result might be devastating.

How are these risks related to malaria in the UK and climate change? The answer is probability. Malaria was common in the in Northern Europe including UK, Sweden and Finland 250-100 years ago, but is no longer a problem. While temperatures declined or showed no trend from about 1750 to the 1920s they have risen since, and we have seen no resurgence of malaria in Europe (except from small outbreaks).

Let us go back to the car. The risk, or probability, of serious injuries in a car crash is dependent on many factors. Increasing the speed will increase the risk, but how do we compare driving a car at 40 MPH without a seat belt to driving the a car at 50 MPH with a seatbelt? From 1750 to 2013 Europe got seat belts and air bags preventing malaria; better houses (less mosquito contact), improved health systems (shorter time to recovery), the population density increased (less mosquitoes per human), and land use changed (less breeding sites for mosquitoes). These factors allowed us to increase the air temperature without increasing the risk of malaria epidemics. So what about the future?

It is virtually certain temperatures will continue to increase the next 100 years. The temperature increase alone will potentially lead to more malaria. But the real impact? Do we assume UK has the same health system in 2100 as today? Will people live in even better houses? What if there is a war in 2080? The IPCC does not make assumptions or scenarios describing alternative realities (on national scales) on how societies will develop the next 100 years. To understand the possible real, and not only theoretical, impacts of climate change, we must also dare to speculate about how society will evolve over the next 100 years. Only then we can come closer to understanding the risk of increasing the speed from 40 to 50 MPH, and know under which assumptions we are making projections about impacts of climate change.

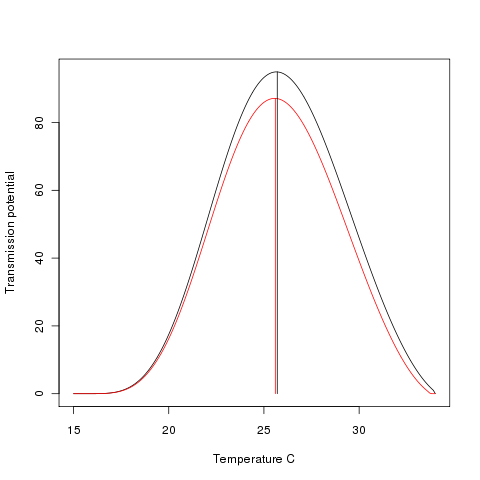

Yesterday an article by Lyons et al., “Stable and fluctuating temperature effects on the development rate and survival of two malaria vectors, Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles funestus“, was published in Parasites & Vectors. This study is important to understand how climate change, changes in temperature between seasons, and from year-to-year influence the transmission of malaria. In this context it is interesting to see if the new data on Anopheles arabiensis alters the conclusion at which malaria is most efficiently transmitted. We refitted the egg-to-adult survival probability and mosquito development rate models described by Mordecai et al. with the data from the paper by Lyons et al., and calculated R0 according to temperature. While the old estimates for Anopheles gambiae s.s. suggested malaria is most efficiently transmitted at 25.6 C, the new data suggest malaria is most efficiently transmitted (by Anopheles arabiensis) at 25.7 C. The plot is showing transmission potential at the y-axis, and temperature in C at the x-axis. The red line is the estimate by Mordecai et al., while the black line is the estimate with the new data on Anopheles arabiensis.

In a recent study in Nature Climate Change Haywood and colleagues demonstrate how volcanic eruptions can influence Sahelian precipitation. Sadly the article is not open access, but from the abstract it seems like they are providing further evidence that aerosols are important for rainfall in the Sahel. In this context I also recommend the study by Huang which shows how black carbon also is a player in this game.

Haywood and colleagues suggest that sporadic volcanic eruptions in the Northern Hemisphere cause Sahelian drought. Using de-trended observations from 1900 to 2010, they show that three of the four driest Sahelian summers were preceded by substantial Northern Hemisphere volcanic eruptions. They used a state-of-the-art coupled global atmosphere–ocean model to simulate both episodic volcanic eruptions and geoengineering by continuous deliberate injection into the stratosphere. In either case, large asymmetric stratospheric aerosol loadings concentrated in the Northern Hemisphere were a harbinger of Sahelian drought whereas those concentrated in the Southern Hemisphere induce a greening of the Sahel.

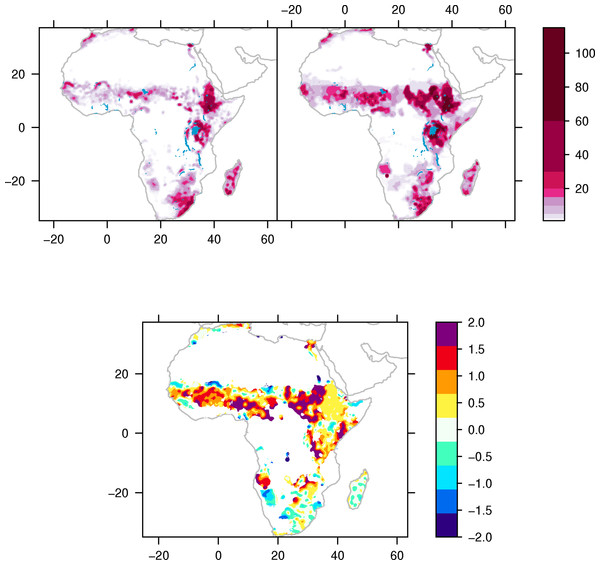

The role of cattle in developing countries is as a source of high-quality food, as draft animals, and as a source of manure and fuel. Cattle represent important contribution to household incomes, and in drought prone areas they can act as an insurance against weather risk. So far, no studies have addressed how historical variations in temperature and rainfall have influenced cattle populations in Africa. The focus of this study is to assess the historical impact of climate variability on national cattle holdings. We reconstruct the cattle density and distribution for two time periods; 1955–1960 and 2000–2005. Based on estimates from FAO and official numbers, we generated a time series of cattle densities from 1961–2008, and compared these data with precipitation and temperature anomalies for the same period. We show that from 1961–2008 rainfall and temperature have been modulating, and occasionally controlling, the number of cattle in Africa.

Working on a malaria model, where one of the abilities is to evaluate the impact of climate change, I have twisted my brain to understand how we should evaluate the impacts of a warmer planet. Sea level rise, fair enough; low lying land might potentially become flooded; the nature of precipitation might influence energy production; ice free Arctic might allow ships to take a shorter route. How climate influence human and livestock health is a more complicated question, and I believe we need to make some assumptions to evaluate the consequences.

When assessing how climate might change in the future, climate modellers have made assumptions, and work from the thinking that if emissions of green house constitutes continue as today, the planet will become X degrees warmer. If we cut emissions today, the temperatures will only increase by Y degrees. To understand how human health is influenced by a changing climate my personal opinion is that impact modellers should adopt the thinking from the climate community, and develop standardized scenarios about population growth, how housing improves (or not), how health systems change, irrigation, … The scenarios needs to be structured on grids, like the climate models. By having this type of standardized scenarios, we will be able to estimate the uncertainty of the impact models, and potentially draw some conclusions about how climate influence human and animal populations.

The 2010 paper by Gething et al. is a good example of how real world projections might become wrong when the society develops along with climate change. A malaria model using a scenario suggesting Europe and the Americas improved housing and health systems would probably come up with the same results as they find in their paper, but very few models take such changes into consideration. This type of scenarios become even more relevant as it seems like we are moving towards adaptation, while emissions carry on like before.